Despite Good Intentions, New Legislation Threatens Livelihood of Indian Street Vendors

– By Emma Rowe (a participant in the Winter School 2013, conducted by the Centre for Civil Society, New Delhi & Centre for Public Policy Research, Kochi)

Plight of the Indian street vendor

The vast majority of the 10 million street vendors in India are forced into an illegal status as a result of strict regulations and licensing caps. They live under the constant threat of harassment and extortion by public officers and gangs and run the risks of fines and confiscation of their goods, which threaten their very livelihoods. The Street Vendor Bill 2012 that was introduced in the last session of Parliament aims to address these concerns by providing street vendors with social security and livelihood rights. Despite these good intentions, the Bill also legally endorses the eviction of vendors and confiscation of their property in poorly defined circumstances. What vendors thought would free them from a state of uncertainty actually hands more power to officers to continue with their harassment.

Currently, vendors are being fined Rs 1,200 for any offence, a disproportionate amount compared with what the average vendor makes in a day. The new Bill states that the penalty may be up to Rs 2,000, which for some vendors is half of their average monthly income. Eviction and confiscation not only deprive vendors of their working capital, they also lead to a loss of their savings and assets, further limiting their ability to make a living.

Appreciating the street vendor ecosystem

While authorities may see street vendors as a public nuisance, it is important to recognize that they play a vital role in the urban economy. The market is a complex system of which vendors are one of many interconnected components; not only do they generate employment for themselves, they provide efficient distribution systems for small-scale producers, thereby supporting employment in that sector as well. Consumers also benefit from their high volume, low margin business model; lower income households, for example, spend a higher proportion of their income on purchases from street vendors due to their affordability. Street vendors contribute to an improvement in the lot of the urban poor by effectively providing them a subsidy in the form of cheaper products.

Eviction of vendors as allowed by the Bill will result in loss of livelihood for many smaller suppliers, and consumers will lose their cheap source of daily necessities. It is low-income households, which have the most at stake and which stand to lose the most when policies are directed against vendors.

Issues do arise when vendors’ activities obstruct pavements or encroach on roads. Crowded footpaths can lead to pedestrians walking on busy roads, and in a country with high pedestrian fatalities, the street vendor is made an easy scapegoat. Pedestrians do deserve consideration, as their safety should take precedence over any other interests. The assumption, however, that vendors are mainly responsible for cluttered footpaths and roads overlooks the fact that pedestrian facilities are awfully lacking in Indian cities. In many places footpaths are poorly maintained or non-existent. Even in areas where there are footpaths, they are often either too narrow or too high, forcing pedestrians to walk on the road. The roads themselves are often cluttered with vehicles. If public money were efficiently directed towards city improvements there could be better pavements and space to accommodate vendors and pedestrians alike.

Residents and shop keepers complain about the crowds and rubbish created by vendors. More often than not those same parties encroach on public space by erecting fences, planting trees and placing signs on pavements. But these forms of encroachment are condoned by authorities in the name of beautification despite the fact that they can hinder pedestrian movements as much as the presence of vendors. This lack of even-handedness in law enforcement often adds insult to injury when it comes to street vending.

A basic role of the Government should be to facilitate conditions that enable people to generate income and secure their livelihoods. Since the Government cannot provide jobs for all, the least it can do is create an environment within which the urban poor can earn their living with dignity. Legal endorsement of eviction and confiscation will not only create uncertainty for vendors, it will also run counter to positive measures the government has introduced to reduce poverty. The Government should create an urban plan that incorporates street vending in its long-term objectives. It should provide conditions where people of all levels of society can prosper.

Lessons from abroad

In the United States, social scientists and public health officials have linked many health problems prevalent in certain areas to food deserts – neighborhoods where residents have limited access to fresh produce. These food deserts are found mainly in low-income neighborhoods and have been exacerbated by restrictions placed on street vendors who used to operate in those areas.

In some parts of the US, there has been a recent turnaround in sentiment and new food policies have been initiated to address the issue by allowing fruit and vegetable carts to open in neighborhoods regarded as food deserts. Yet, in other areas there continues to be strict enforcement of vending regulations by authorities, which includes arrest, confiscation, and destruction of fresh produce and equipment. These near-daily sweeps undermine access to healthy food and are in complete contradiction to what other government departments are trying to achieve.

The enforcement officers’ actions exacerbate the very same problems the health authorities are trying to combat. The one dimensional public policy approach is a failure on the government’s part to systematically examine the policy processes and their consequences.

Similarly in India, street vendors are the only source of fresh low cost produce in many low-income neighborhoods. So while vending may generate some problems in poorly regulated areas, it is necessary to consider how eviction may result in unforeseen and unwelcome outcomes; the services vendors provide clearly benefit certain aspects of urban life.

A better way

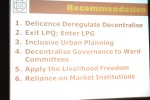

The Bill hands power to local authorities to evict vendors on account of public nuisance, public obstruction or for any other public purpose. Vendors will be given 7 days notice before eviction and will be fined Rs 500 for every day that they fail to relocate from the site. In addition to eviction, their goods can be confiscated if authorities deem it necessary. The conditions under which authorities can evict a vendor are so wide-ranging that the Bill leaves scope for abuse of authority and arbitrary exercise of power. In order to protect the livelihood of vendors as the Bill primarily intends to do, legislation should prevent extortion and bribery. Section 34 of the Police Act already vests adequate powers for law enforcement. Reiterating these powers through the proposed sections on Eviction & Confiscation in the Bill is unnecessary and runs the risk of accommodating further harassment.

The question is whether eviction and confiscation will solve the problem of repeated offending. Certainly some regulations must be put in place in order to protect the rights of other users of the road, however discovering the root cause of the offences is likely to be better for all parties. Perhaps vendors breach the rules because the local authorities have placed them in areas away from their natural markets, forcing them to move beyond their designated areas.

If this is the case, it could become a real issue down the line as the Bill hands local authorities the power to determine vending zones. Developing informational workshops to provide street vendors the necessary knowledge to earn a living while complying with the law would be a more suitable and long-term solution than eviction. In this regard the Bill is to be commended for its recognition of the desirability of capacity building programmes, and the Government should ensure that it provides adequate support in terms of budgets and facilities to leverage the potential of these workshops.

In addition to vending zones, the Bill empowers local authorities to prescribe the hours that vendors are allowed to operate. Vendors work long hours in order to make a decent living. Restrictions on the hours in which they can work may significantly impact their ability to achieve this. Under the proposed legislation, vendors may be fined up to Rs 2,000 for vending beyond their designated zones and timings.

The workshops should also provide feedback mechanisms for the vendors to negotiate the times allocated to them. There should be flexibility within the scheme to incorporate the nature of their business. For example, a particular vendor’s product may be in demand only in the evening; it would therefore be unjust to deprive the vendor the opportunity to operate during that time frame.

As a cost saving measure for the government, these workshops could be organized in association with existing vendor unions and NGOs. These organizations would be in the best position to run the workshops as they work closely with the vendors and would be more aware of their requirements. They would also be able to cater for the different levels of education amongst the vendors and establish courses that were sensitive to their various backgrounds and capabilities. This type of approach is crucial, as a one-size-fits-all program will not address the diverse needs of different types of vendors.

Infrastructure is key

Vendors are a product of the market and will continue to exist as long as there is a demand for their services. Vendors are still very much a part of the culture in even the most developed countries and in many cases are a feature of a city that attracts many tourists. Therefore in new developments, it would be worth considering allocating areas for street vending and providing sufficient sidewalks, not only for the vendors but for the sake of pedestrians in general.

There have been various studies and experimentation on how new development designs can incorporate vendors. First and foremost, all stakeholders must be part of the consultation process; inviting stakeholders to discuss the design can lead to greater understanding amongst the parties. City “beautification” schemes should accommodate the needs of vendors, as these projects will not be successful without their cooperation.

In South Africa, redevelopment of a vendor market showed that investing in infrastructure for vendors lead to longer-term prosperity. A kiosk with electricity and water enables vendors to generate more income; vendors are able to increase their stock and use the kiosk as a storage unit, which saves both storage costs and time that would otherwise be spent packing and unpacking products. In India, the various vendor organizations could provide vendors with the initial capital to purchase these types of kiosks.

Threat of harassment and eviction can act as disincentives for vendors to devote time to the upkeep of their vending areas; security of tenure will more likely motivate vendors to maintain clean and hygienic spaces and to develop a sense of pride and ownership of their workplaces. Therefore in order to fulfill the defined objectives of the Bill, eviction should ultimately be the very last resort. In the event that relocation becomes absolutely necessary, the authorities should provide a notice period of at least 30 days rather than the 7 days that is currently prescribed in the Bill.